(The following is taken from a text called ‘What are the Digital Posthumanities?’. It forms the basis of a chapter of a book I’m working on, the provisional title of which is Pirate Philosophy. Zombie Materialism I: Derrida vs Deleuze? is available here, and Zombie Materialism II: New Materialism here)

The reason I am interested in the kind prejudice regarding theory I outlined in Zombie Materialism II: New Materialism, is not out of some stubborn refusal to move on and get with the new materialist programme, and insistence on staying where I am by defending the legacy of Derrida and deconstruction - and even, dare I say it, suggesting it be re-engaged. As one of the co-founders of Open Humanities Press I’m partly responsible for the publication of two book series - Graham Harman and Bruno Latour’s New Metaphysics, and Tom Cohen and Claire Colbrook’s Critical Climate Change - that could in their different ways both be said to share Rosi Braidotti’s ‘impatience’ with deconstruction. (Moreover, at least one of these series is explicitly associated with new materialism: Rick Dolphin and Iris van der Tuin’s New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies appears in New Metaphysics, and includes interviews with Manuel DeLanda, Karen Barad, and Quentin Meillassoux, as well as Braidotti herself.)

Nor should any of this be taken as implying that, rather than raising the question of what it means for our ways of being as theorists and philosophers if writing, print-on-paper and the codex book are not regarded as the ‘natural’ or normative media in which ‘theoretical’ research and scholarship are conducted - a question that, as we have seen, can be said to represent part of posthumanism’s own repressed - we should instead continue to concentrate on writing linearly structured, original, fixed and final print-on-paper texts, in uniform multiple-copy editions, on an all rights reserved basis, on the grounds that these too can be considered to be intricately bound up with the material. One of the reasons I’m interested in Derrida (together with Bergson, Deleuze, Braidotti et al) is because his philosophy has the potential to help those of us who are not resistant to thinking through the conditions and assumptions of our own disciplines (such as those that do indeed have to do with writing, print-on-paper and the codex), and who are open to denaturalizing and destabilizing disciplinary formations (including those associated with theory), to avoid slipping into such anti-political moralism ourselves. It can do so by virtue of the way, in its attention to detail and rigour, it teaches us not only to read and (re)write texts hospitably and responsibly. It also encourages us to pay careful attention to how arguments such as those around materiality (and the need to focus on software, hardware, life, biology, genetics, ecology, the environment, electronic waste and so on) are more often than not conducted in the very language and writing that such new materialism is ostensibly trying to move us on from. In addition, Derrida’s philosophy can help us to avoid the kind of moralism that can be detected in many theories of materialism through the emphasis it places on paying close attention, not just to reading, writing, language and the text - and with them, as we shall see, to the critical and creative rethinking of concepts such as precisely writing, language, text, materiality, matter - but to their material properties, practices and processes of production as well.

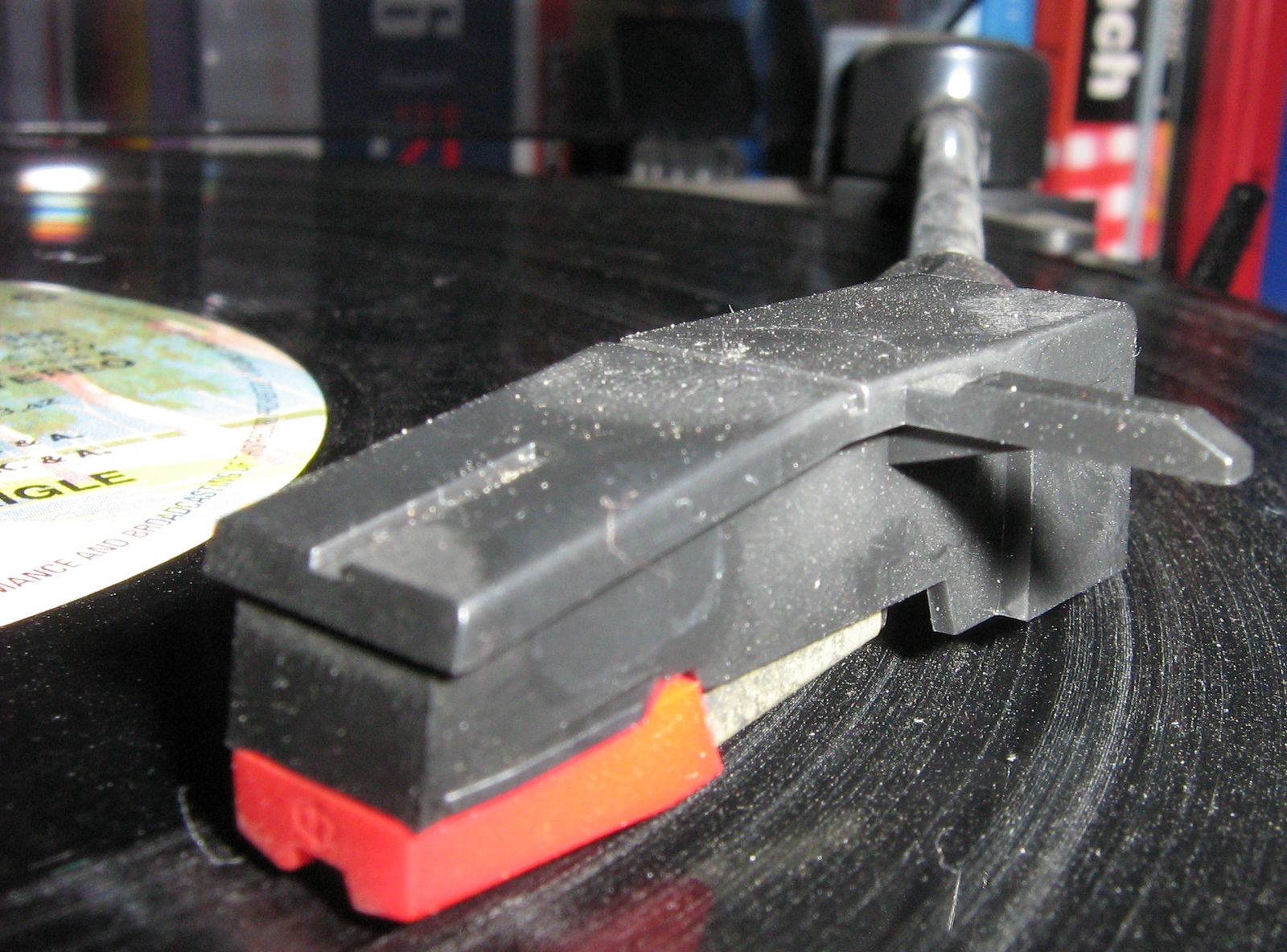

Witness the care he devotes to considerations of the stylus or writing instrument, the pen, typewriter (first mechanical then electric), and word processor, the signature, paper, the letter, postcard, ‘mystic wax writing pad’, the book and of course its ‘inside matter’, as well as to the institutions of literature, philosophy and the university. And that is without even mentioning Derrida’s various creative experiments with the material form, format, size and shape of his texts: the use of multiple columns, extended footnotes and so forth in works such as Dissemination, The Post Card, Glas, ‘Tympan’ and ‘Circumfession’.

It thus comes as no surprise to discover that not all materialists have succumbed to the tendency of zombie theory to position deconstruction in terms of the limitations of its concern with text, signification and the linguistic. In Quantum Anthropologies, Vicki Kirby adopts an highly sophisticated materialist approach to reading the legacy of Derrida in order to ‘recast the question of the anthropological – the human – in a more profound and destabilizing way than its disciplinary frame will allow’. Kirby proceeds to criticize as naïve, complacent and lacking in rigour John Protevi’s claim in Political Physics that Derrida’s ‘general text… while inextricably binding force and signification in “making sense””, is not an engagement with matter itself’. In fact, an engagement of this nature is not possible, if Protevi is to believed, since matter, for deconstruction, ‘remains a concept, a philosopheme to be read in the text of metaphysics’, or else ‘functions as a marker of a radical alterity outside the oppositions that make up the text of metaphysics’. Kirby condemns this account of deconstruction on Protevi’s part on the grounds that the assumption ‘Derrida's "no outside metaphysics" must exclude matter… entirely misses the extraordinary puzzle of how a system's apparent interiority can incorporate what appears to be separate and different.’ As far as Kirby is concerned, while ‘"text“ and "metaphysics" are sites of excavation, discovery, and reinvention for Derrida, Protevi uncritically embraces their received meanings’.

There are many Deleuze's

It is also worth pointing out that not all Deleuzian’s have adopted a moralistic approach to materialism. If, for Kirby, ‘there are many Derrida’s’, then there are many Deleuze’s too! One of the most interesting articulations of a materialist ontology inspired by Bergson and Deleuze is that provided by Tim Ingold, another anthropologist, in an essay called ‘Materials Against Materiality’ that can be found in his book, Being Alive. Ingold notes how, despite the impression it gives, ‘the ever-growing literature … that deals explicitly with the subjects of materiality and material culture seems to have hardly anything to say about materials’: about the very matter of bodies, non-human objects and the environment. Instead, the concern of those emphasizing the importance of materiality is primarily with the language and writing of other theorists and philosophers. The materials meanwhile have gone missing.

As his title suggests, Ingold recommends a shift in attention from ‘the materiality of objects’ precisely to ‘the properties of materials’. It is a shift that once made is capable of exposing:

a tangled web of meandrine complexity, in which – among a myriad of other things – the secretions of gall wasps get caught up with old iron, acacia sap, goose feathers and calf-skins, and the residue from heated limestone mixes with emissions from pigs, cattle, hens and bees. For materials such as these do not present themselves as tokens of some common essence – materiality – that endows every worldly entity with its ‘objectness’; rather, they partake in the very processes of the world’s ongoing generation and regeneration, of which things such as manuscripts or house-fronts are impermanent by-products.

Hopefully all this explains why I do not want to oppose the tradition of Spinoza, Bergson, Deleuze and Guattari to that of Derrida here. It is not hard to see how even a rigorous reading of Deleuze’s materialist philosophy can be employed to show that deconstruction is actually far more concerned with matter, materials and material factors than a lot of erstwhile (new) materialism.

In fact, according to Ingold, far from helping to theorize the material, the concept of materiality as it features in a lot of studies of material culture serves to reinforce, rather than overcome, the classical dualities and dialectical (Latour would call them modern) oppositions between nature and culture, immaterial and material, language and reality, things and words, body and mind. This is because a part of the material world such as a rock or stone tends to be considered by discourses on materiality as ‘both a lump of matter that can be analysed for its physical properties and an object whose significance is drawn from its incorporation into the context of human affairs’. For Ingold, however:

humans figure as much within the context for stones as do stones within the context for humans. And these contexts, far from lying on disparate levels of being, respectively social and natural, are established as overlapping regions of the same world. It is not as though this world were one of brute physicality, of mere matter, until people appeared on the scene to give it form and meaning. Stones, too, have histories, forged in ongoing relations with surroundings that may or may not include human beings and much else besides.

He thus takes great care to distinguish between ‘the material world’ of material culture theorists and a ‘world of materials’ or, better, the environment. The material world exists in and for itself. The environment, by contrast:

is a world that continually unfolds in relation to the beings that make a living there… And as the environment unfolds, so the materials of which it is comprised do not exist – like the objects of the material world – but occur. Thus the properties of materials, regarded as constituents of an environment, cannot be identified as fixed, essential attributes of things, but are rather processual and relational. They are neither objectively determined nor subjectively imagined but practically experienced. In that sense, every property is a condensed story. To describe the properties of materials is to tell the stories of what happens to them as they flow, mix and mutate.

Thursday, May 8, 2014 at 3:53PM

Thursday, May 8, 2014 at 3:53PM